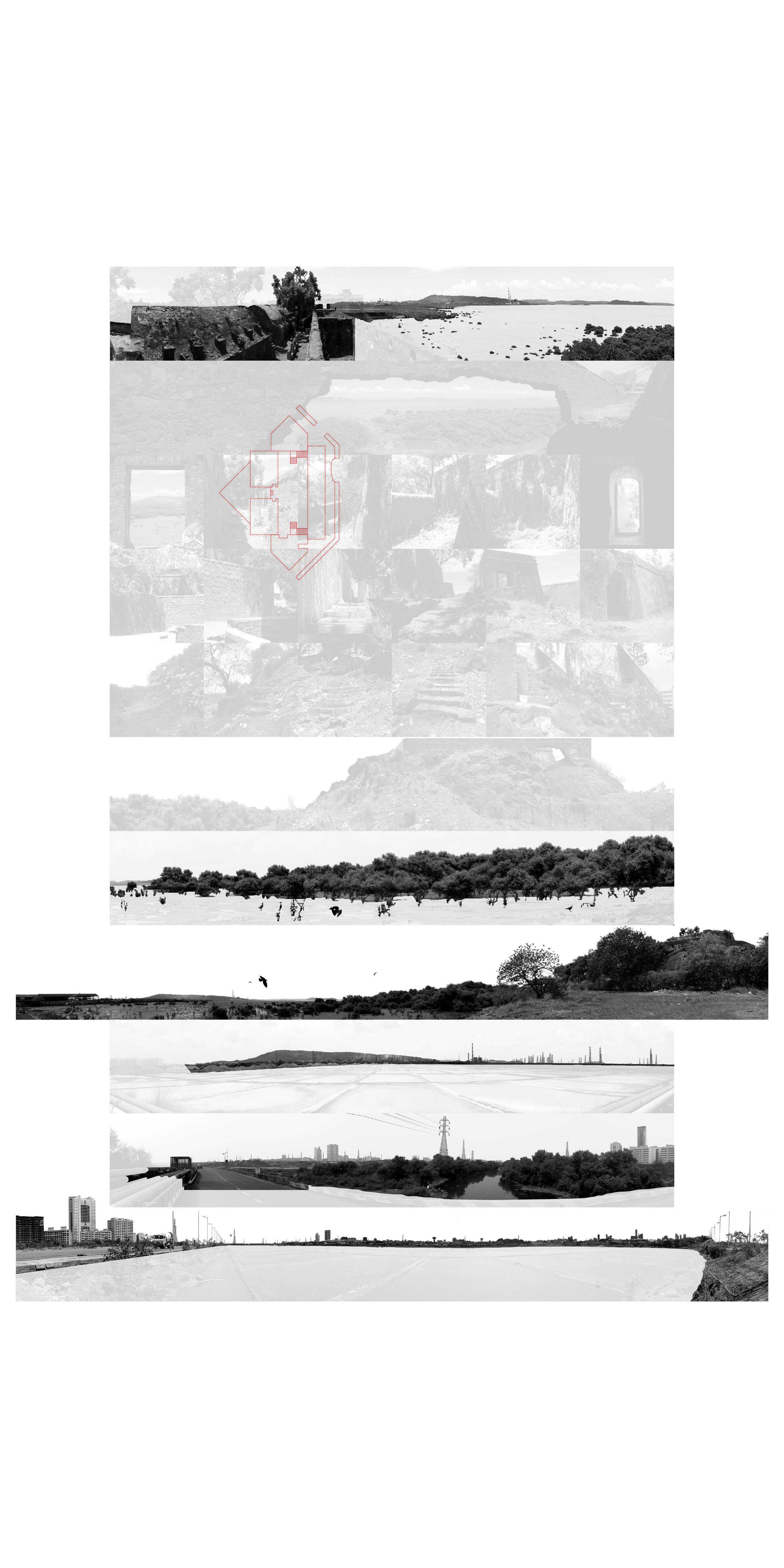

3.1 Creek Forts

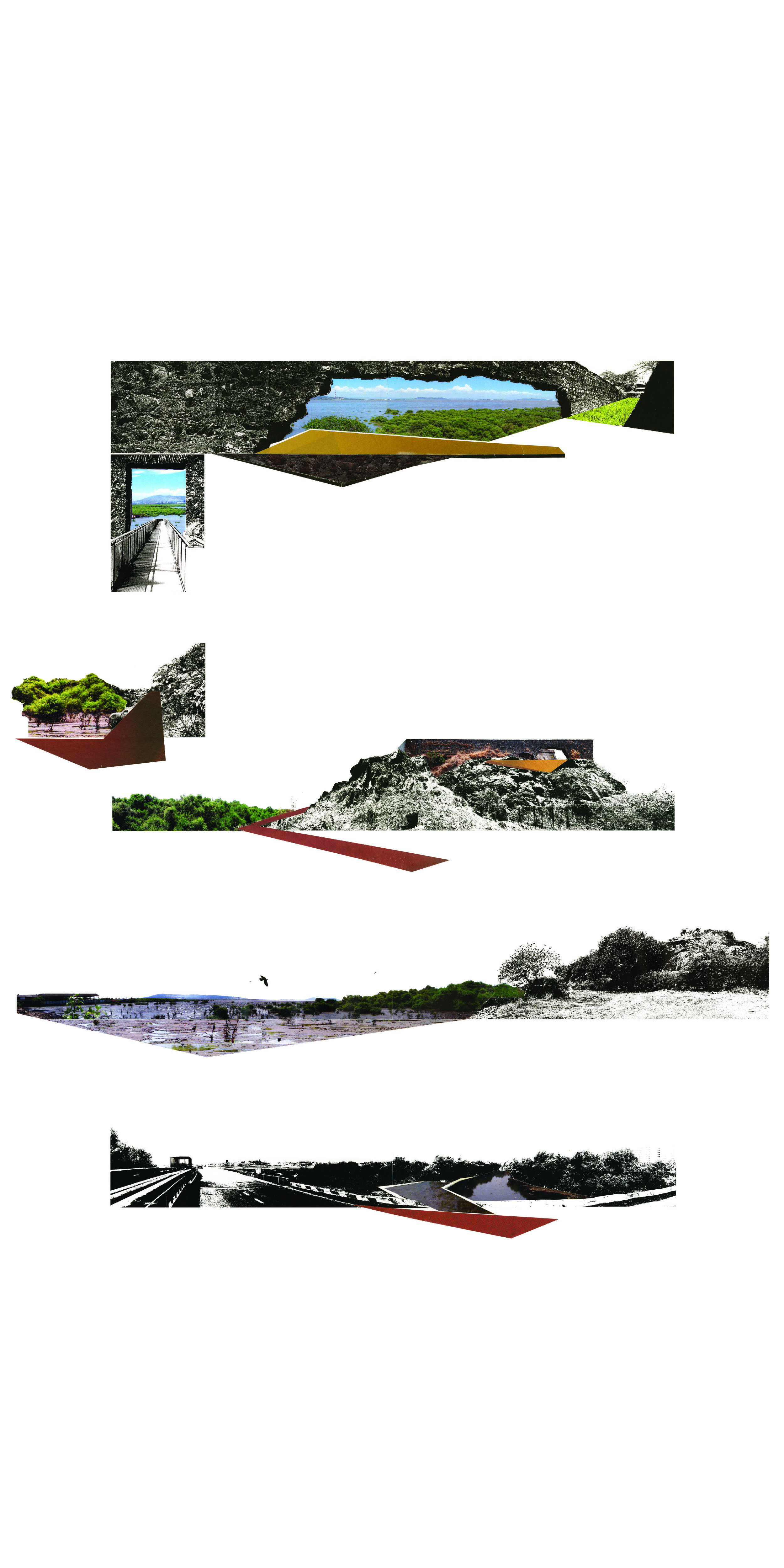

The projects of this section take their starting point from five historic forts that once looked upon Mahim Creek where waters flowed in more than one direction and touched the sea at more than one place: Worli, Mahim, Rewa, Sion and Sewri. Historians see these forts securing the north edge of an island. However, they can also be seen as command points of the creek beyond this edge, their names extending fluidly into one another rather than stopping at a territorial boundary in between. Even though maps show them today consumed by the frontier of landfill, the labyrinth still exists, flowing through settlements and around them, sometimes in pipes, other times in open drains, but most often across a surface of roads, paths, roofs, homes, maidans, beaches, and swamps that gather and dissipate momentarily. These flows are not just of monsoon and saline waters; they are sewage as well.

The five ‘Creek Forts’ with their distinct visual and material horizons take command of these flows: deflecting, extending, treating, filtering, absorbing, monitoring and even initiating them. The processes by which they do so, always in relation to the particular conditions that have materialised on this frontier, open new opportunities and occupancies that revive Mumbai’s ability to accommodate the complex combination of monsoon, sea, and effluent.

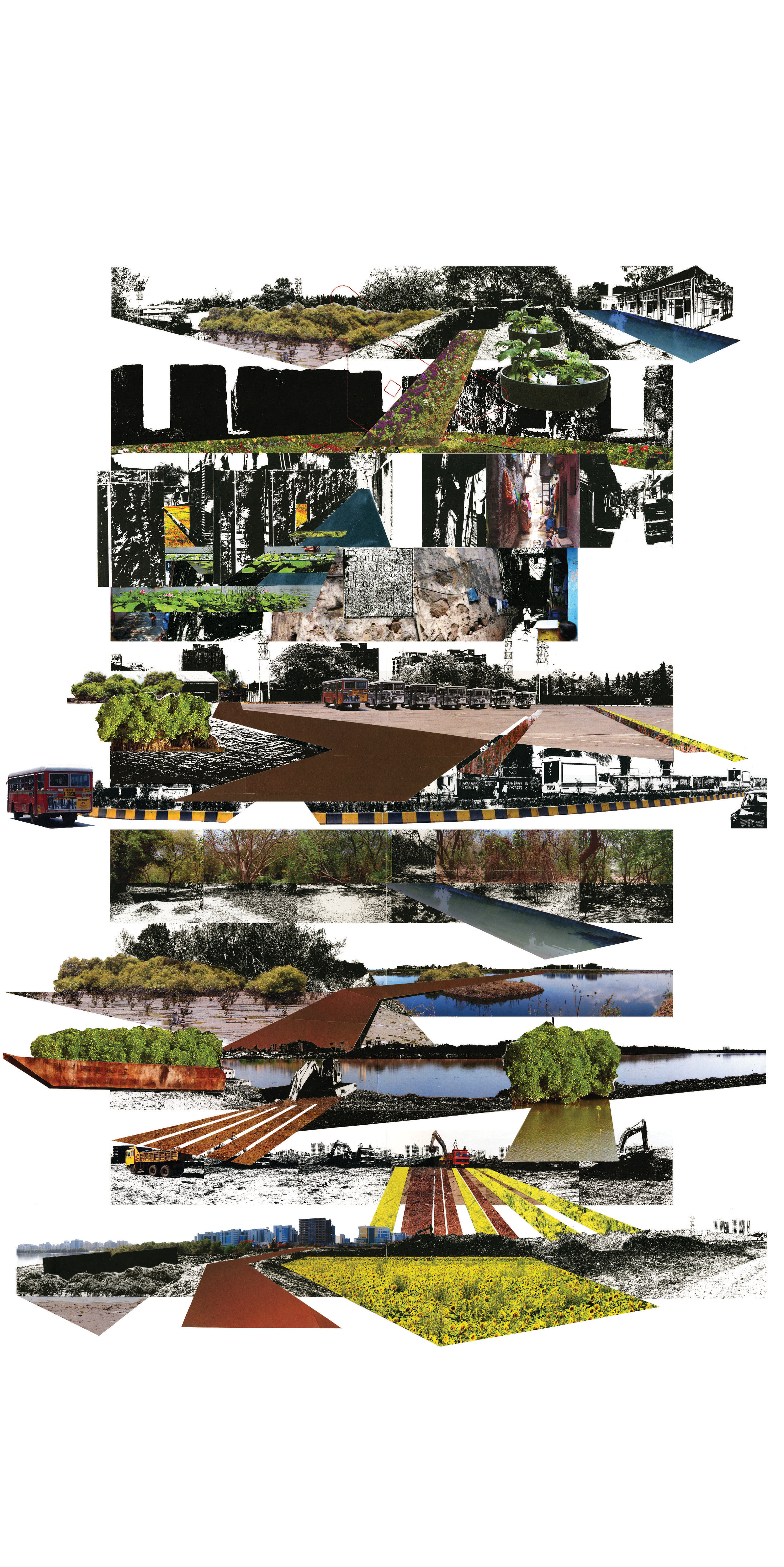

1. Worli Fort

The Worli Fort Project appropriates a portion of a ridge that extends north and south as a series of peaks and troughs, defining the western edge of Mumbai. It is the part inscribed by the movements of a fishing community for whom it is and has been for a long time, a spine of daily activity, connecting one of the earliest settlements in Mumbai south of the fort with a boat ramp down to Mahim Bay north of the fort. The project articulates and thickens this spine, constructing new economies and relationships between the people of Worli and visitors to Worli Fort arriving by sea. With its commanding prospect of sea and bay, the fort serves as a staging ground for local theatre and dance performances, such as the laavni. A walkway extending westward from it anchors stepped terraces that are appropriated as they are to some extent today, for markets, games and drying fish. The walkway extends to a jetty and a field of bio-treating barges anchored under the Bandra-Worli Sea Link. These barges, which are in the last stage of treatment, configure and reconfigure fields/gardens of performance-oriented plants in the process of their circulation between this anchoring ground and stations at Rewa, Mahim, Vakola, Dharavi and the upper bay-side of the Worli peninsula. They can be visited by a public for a walk, an educational moment, or a sunset.

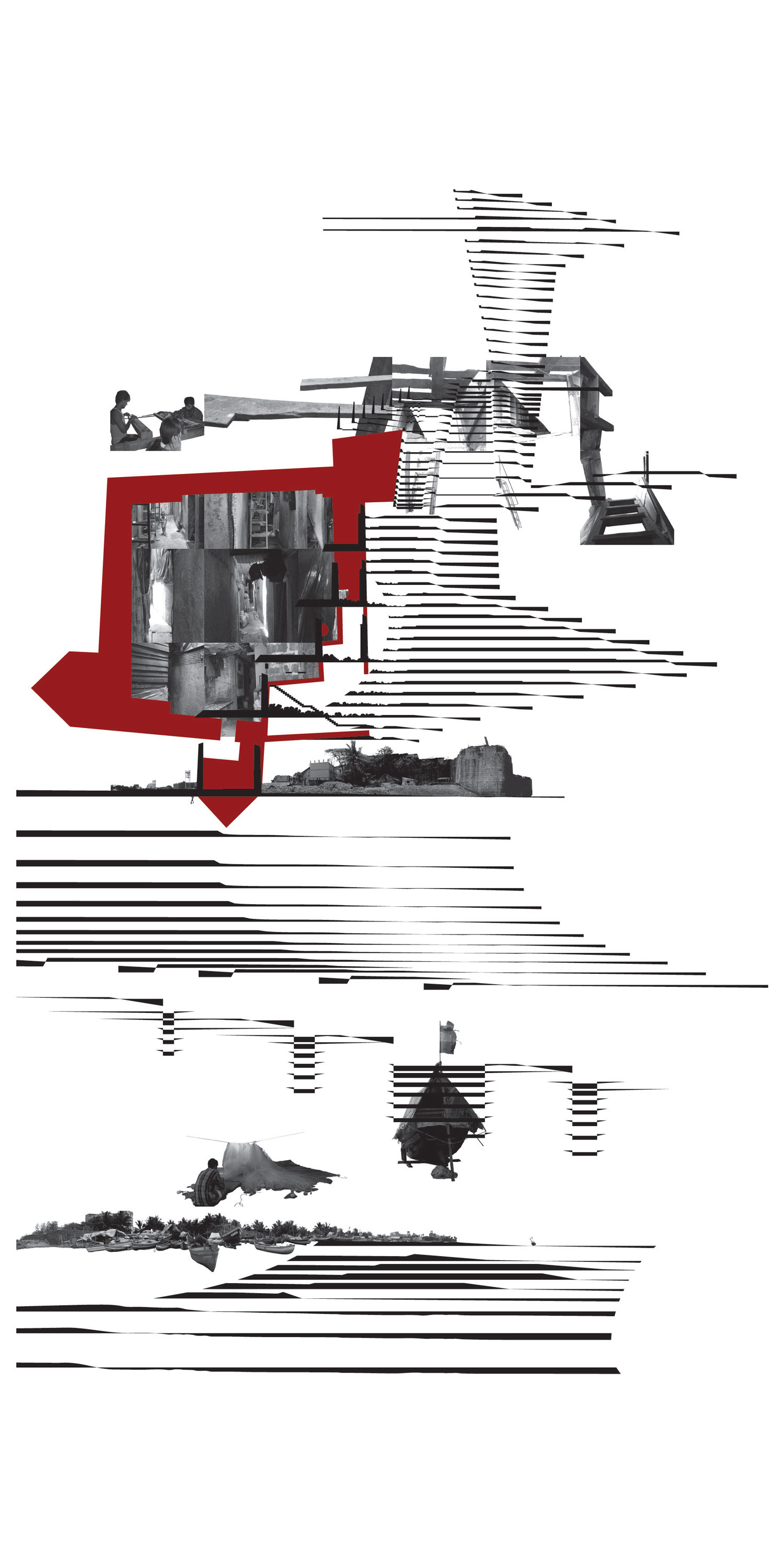

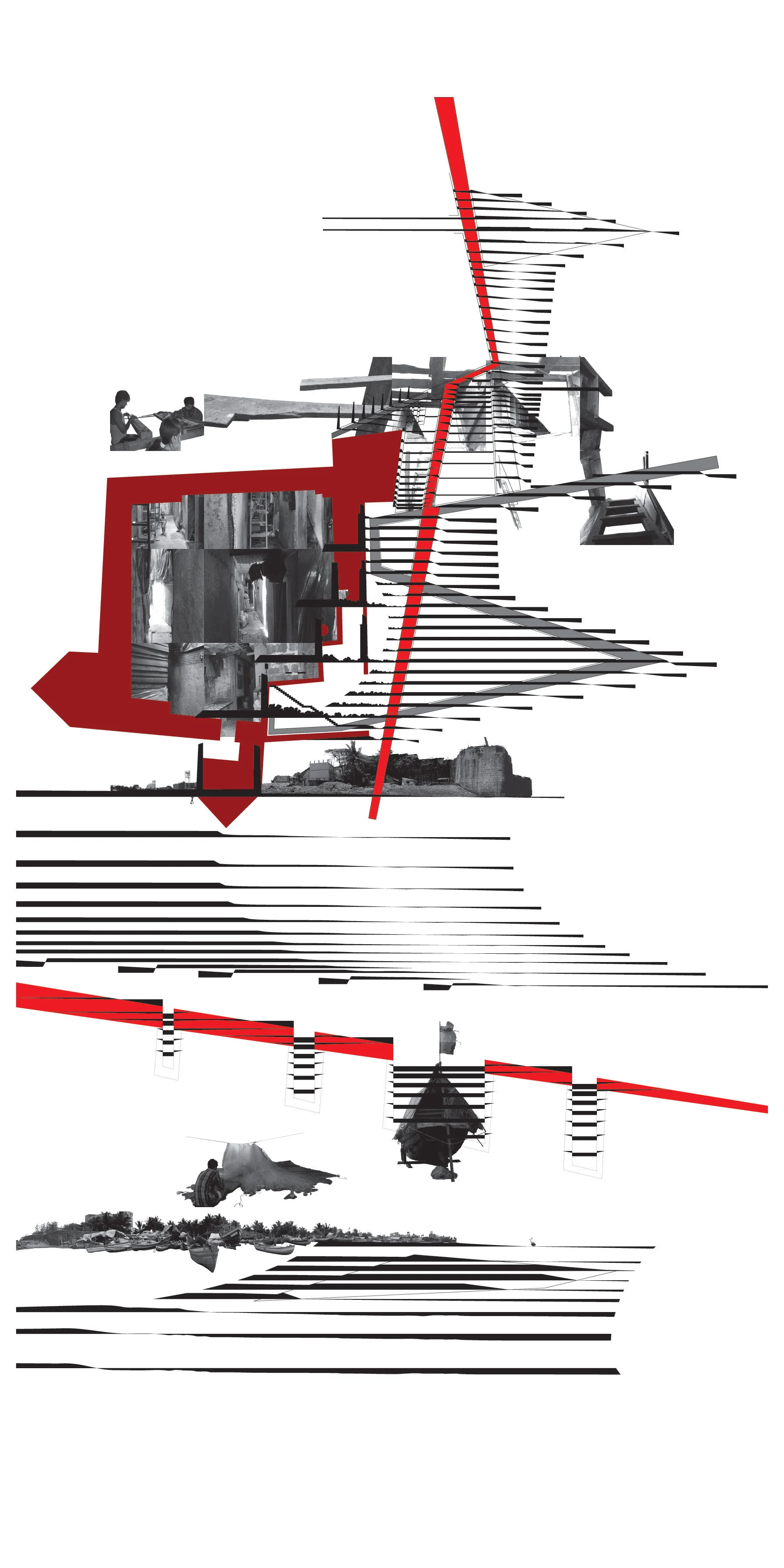

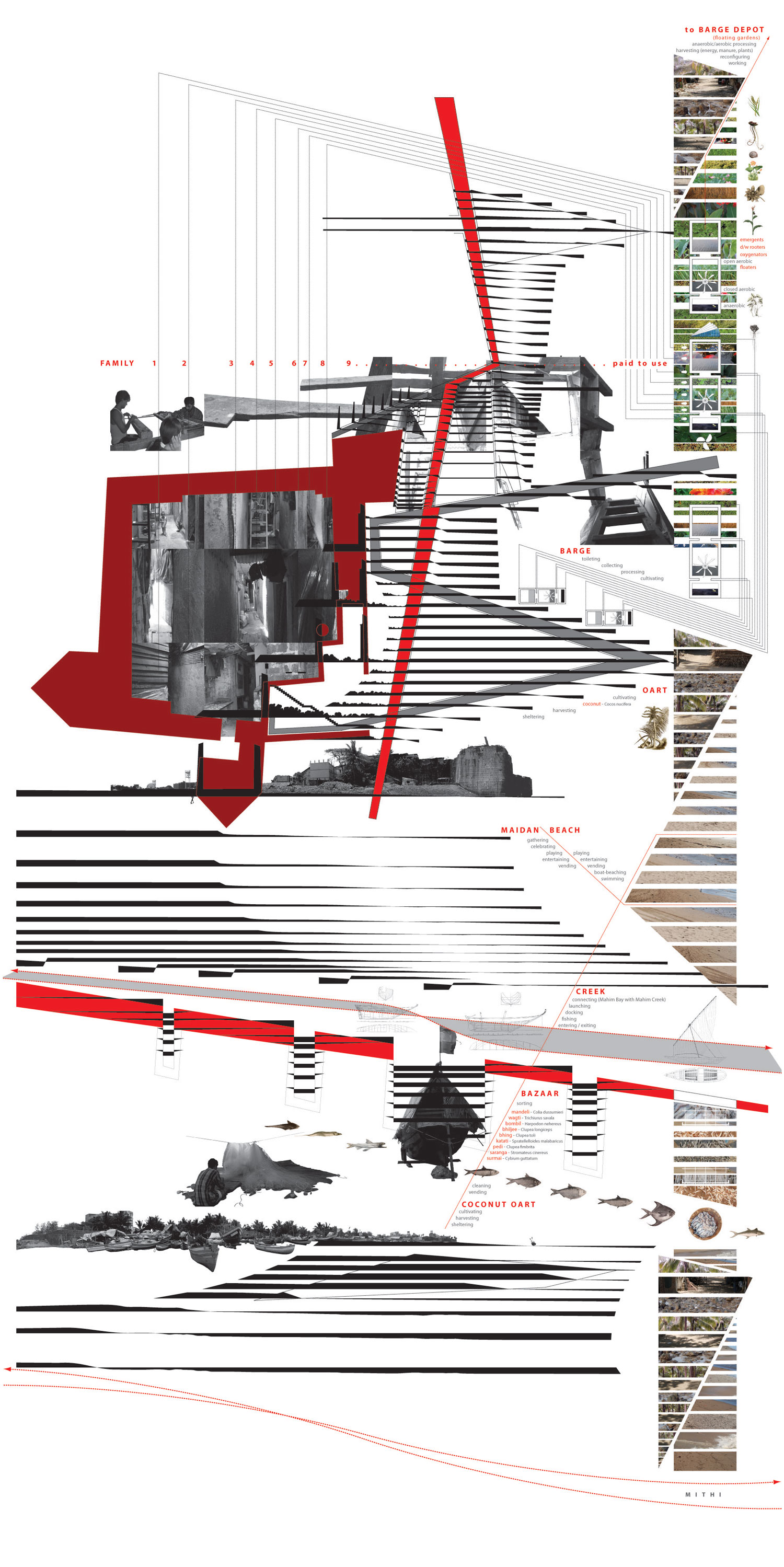

2. Mahim Fort

The Mahim Fort Project intervenes in the trajectory of a moving corner where the east-west flows of Mahim Creek with its finer-grained content of silt and clay meet the north-south edge of a bay with its larger-grained content of sand. This corner, once held by the fort, has moved north with depositions against the causeway built across the creek in the 1840s, making land that has been appropriated for a maidan/beach, a fishing village and a sewage pumping station. The project deflects this northward force that has pinched the creek with interventions that extend in the east-west direction. A new creek cuts opportunistically through the sand bank and settlement toward the east. It links Mahim Bay with the Mithi beyond the causeway, providing the Mithi with another link to the bay while also serving as an axis for docks and a market. Cultivations of coconut palms that support recreational and economic activities within their grove extend and protect the shore from further erosion at the fort and further north along the bay. At the fort and possibly elsewhere, these oarts provide docking facilities for bio-treating barges that anchor here for periods of time with amenities assigned to particular families living in the fort. Paid to use these barges for the energy and the manure that can be harvested from refuse, these families are invited to associate with a system that circulates between these oarts and anchoring grounds offshore where the material gathered is given time to process aerobically and anaerobically into energy, manure and grey waters.

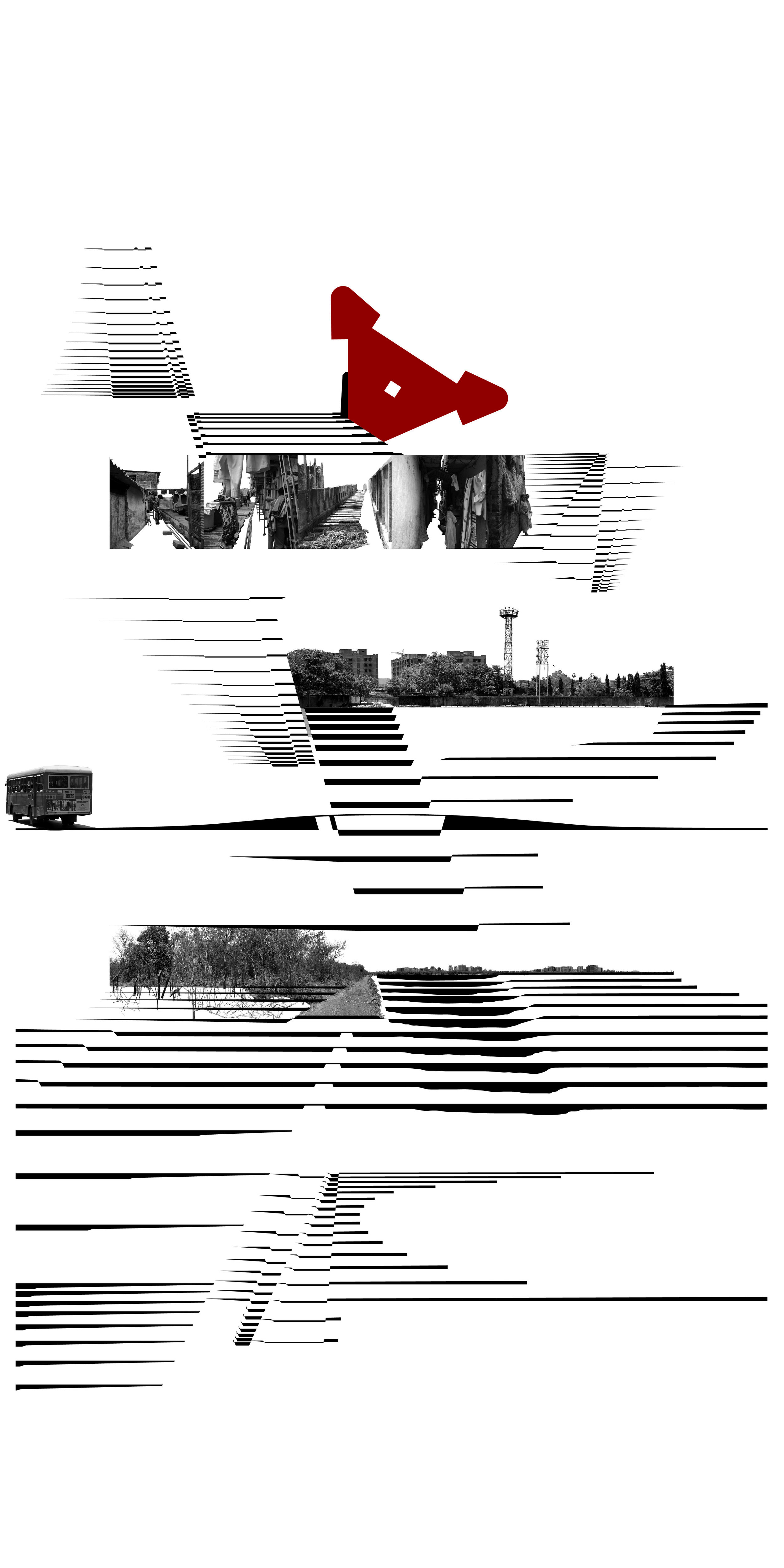

3. Rewa Fort

The Rewa Fort Project is anchored on a trajectory of landfill and settlement which began in the 1700s with the closing of the mud flats that is today central South Mumbai and extended north between Dharavi and Sion. A cut through the debris and garbage that comprises this fill registers this vector and reconnects the Mithi with the fort through Maharashtra Nature Park. This cut is an access for bio-treating barges and a way to initiate salinity gradients in the Park and the surface of the Dharavi Bus Terminal: gradients for mangrove cultivation that would surgically transform the edges of the park and terminal as much as begin a transformation of the estuary at large. On the far side of the Bandra-Kurla Complex, the edge is the basis of a different operation. Here, the dredged material that is removed from deepened pockets made in the bed of the Mithi to serve as silt traps, defines a series of lots that orchestrate a process of gathering, aerating, phyto-remediating and harvesting soil. A pedestrian bridge on axis links this unique working park of soil beds and flower fields, which present a new front to the Bandra Kurla development, with Rewa Fort, which itself serves as a monitoring and information station for water quality, pollutants, and laboratory experiments. While the fort is the culmination of this axis, it is also the head of old and potentially new developments in Dharavi that can deploy their open spaces toward extending an estuary with biotic treatment fields and mangrove parks as the new, yet old, expression of their landscape.

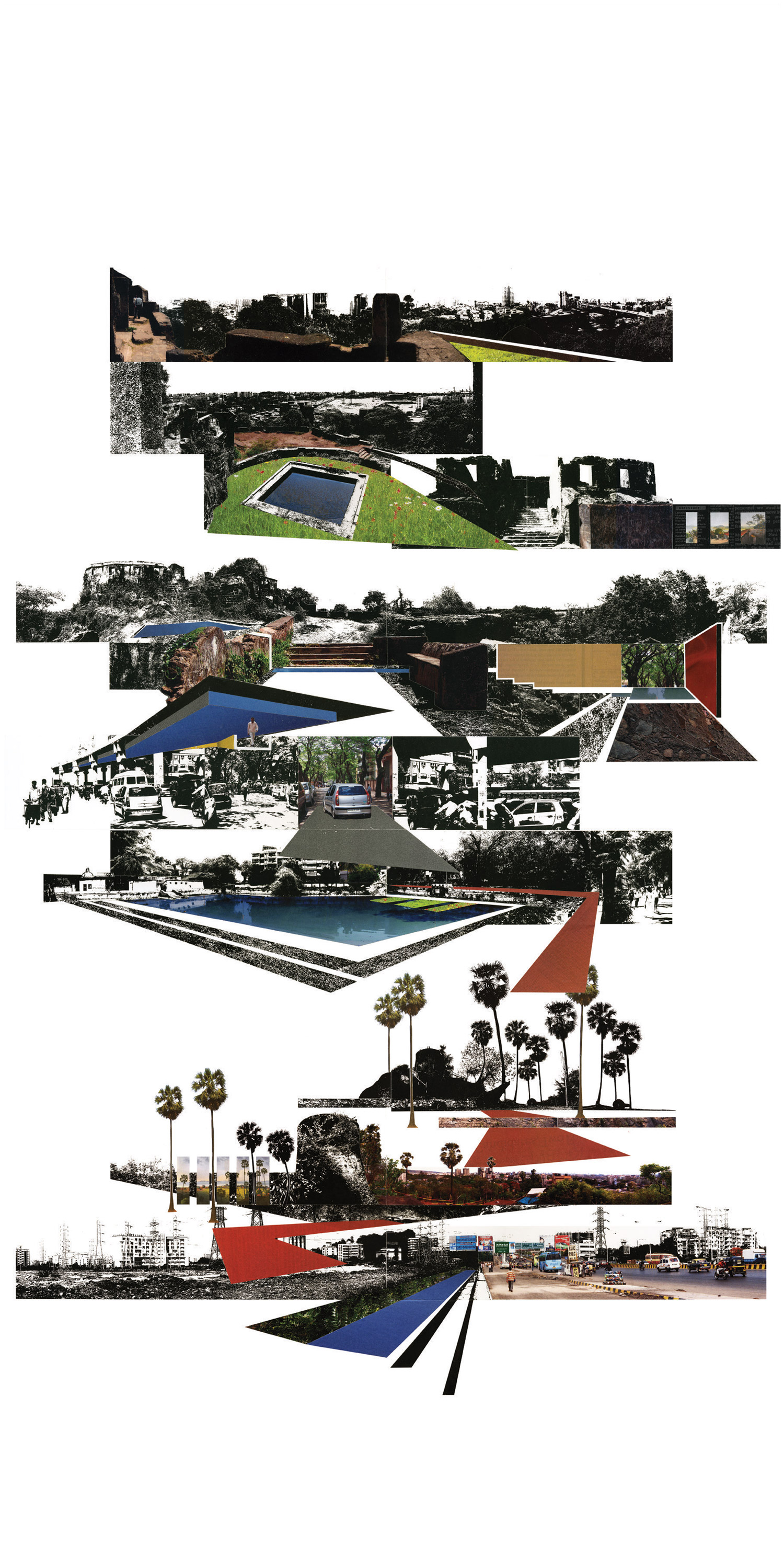

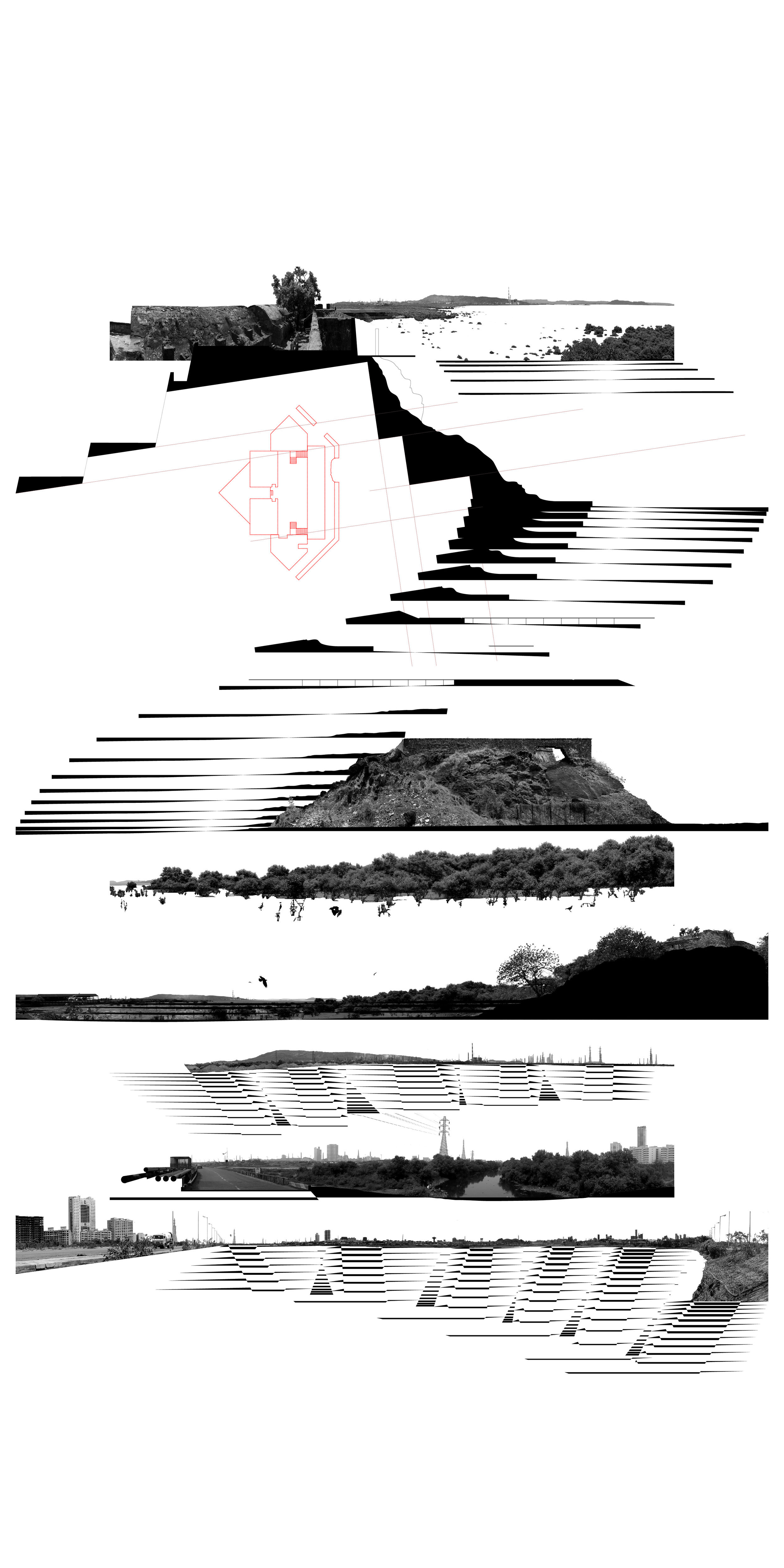

4. Sion Fort

The Sion Fort Project is on a line that begins with the twin peaks of Sion Hill and culminates in the traces of Mahim Creek designed to connect the Mithi and Mahul surfaces (Project 7). One peak of the hill is occupied by the Sion Fort with its commanding view of Mahim, Mumbai and Thane that makes it a possible repository and exhibition ground for the transformations of Mumbai’s landscape. The other peak is topped by a battery that captures the little that is unseen from the fort. The saddle between them is where the Sion-Kurla Causeway once began its crossing (and closing) of the Mahim Creek and where today, the Eastern Expressway comes through. It is also the site of the much neglected Sion Tank that intercepts the waters coming off the slopes. It makes it possible to develop the line from peaks to sea as one of water flow linking a derelict tank within the fort, the cultivated slopes and aquifers of the hill, a tank beneath the raised Eastern Expressway which collects the waters coming off its asphalt surface, the Sion Tank, and a series of biotic treatment fields above and below this tank. The flow, or rather series of overflows, serves as a spine of activity: walks, gardens, and performances.

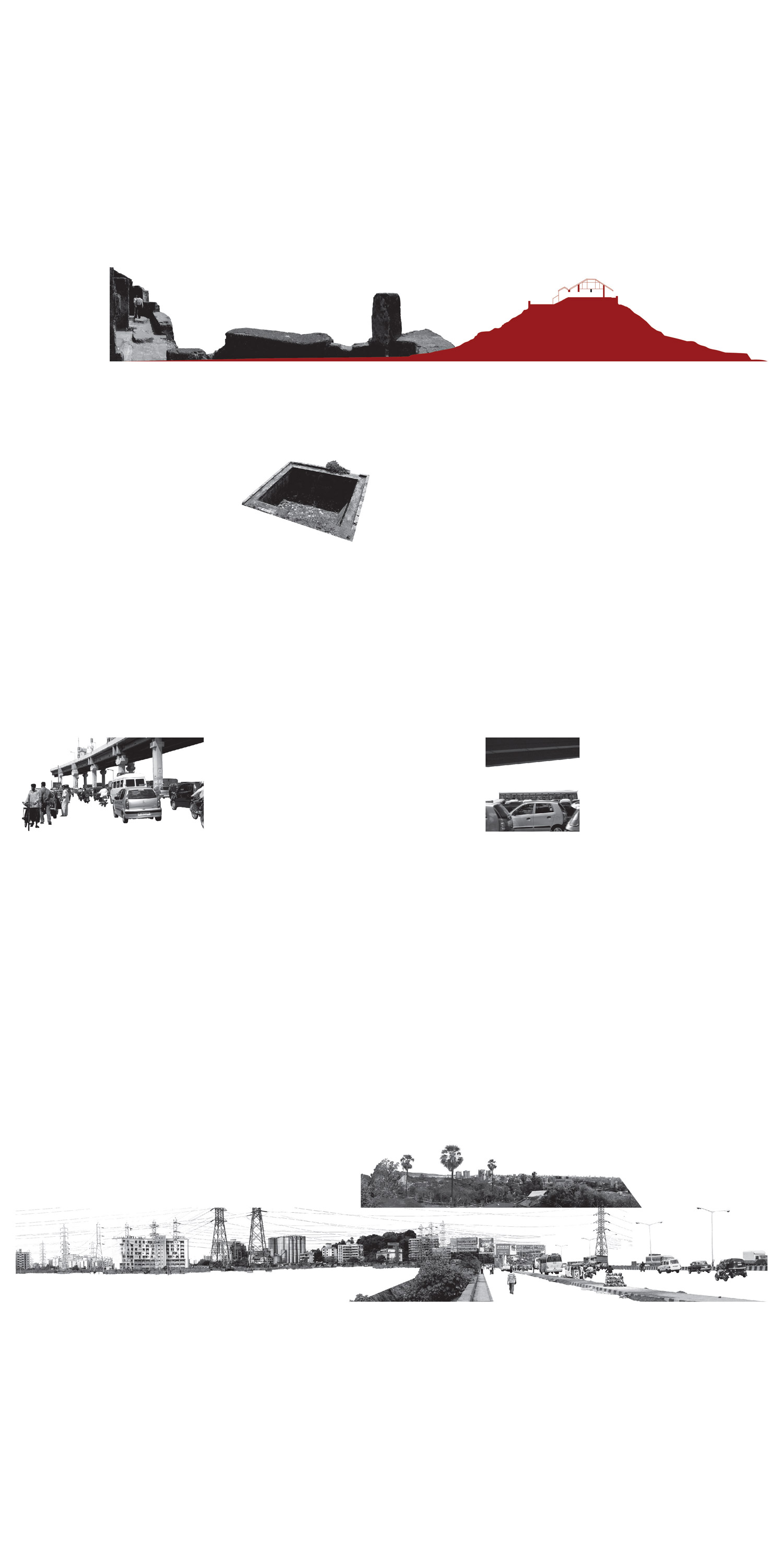

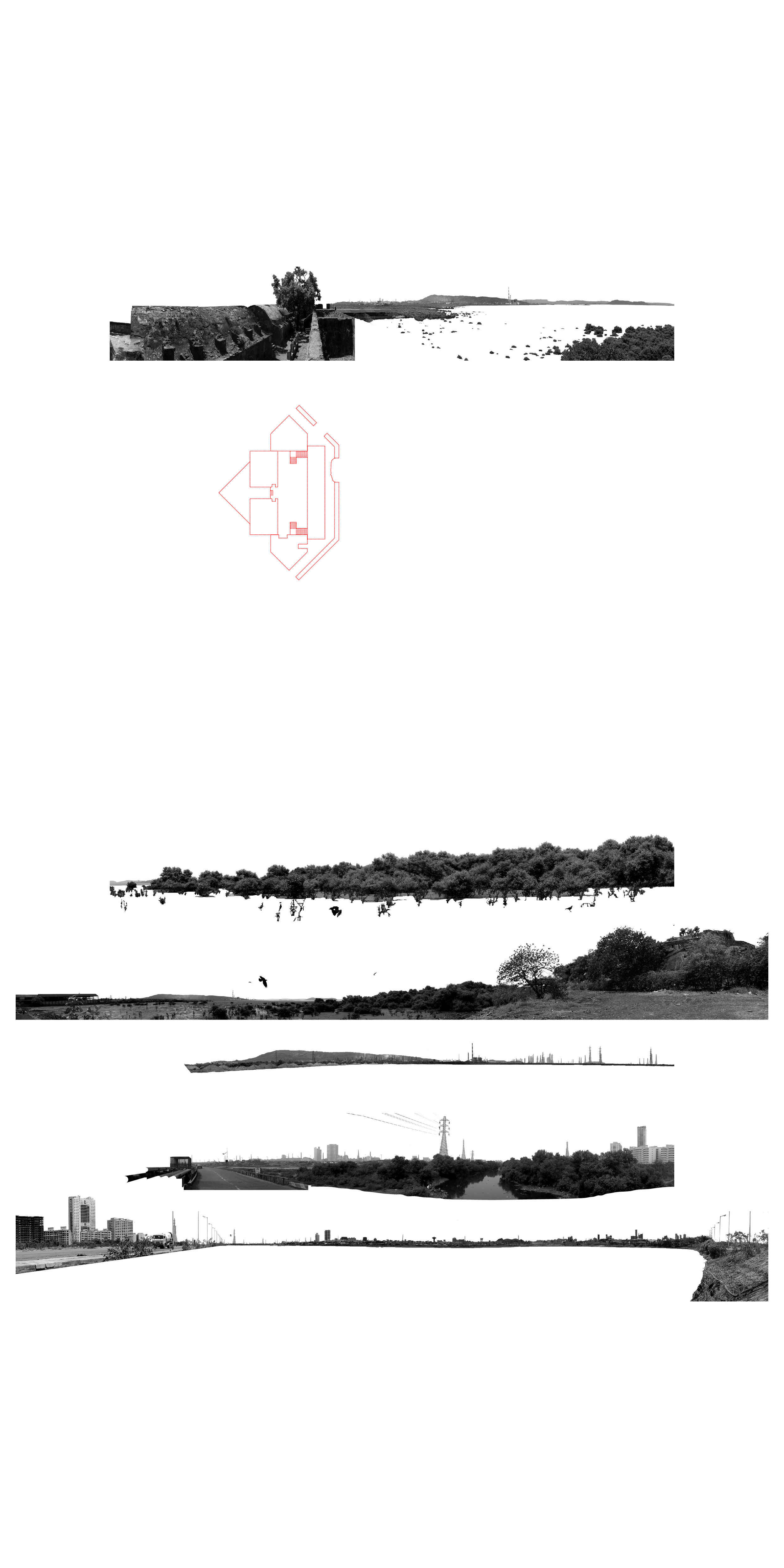

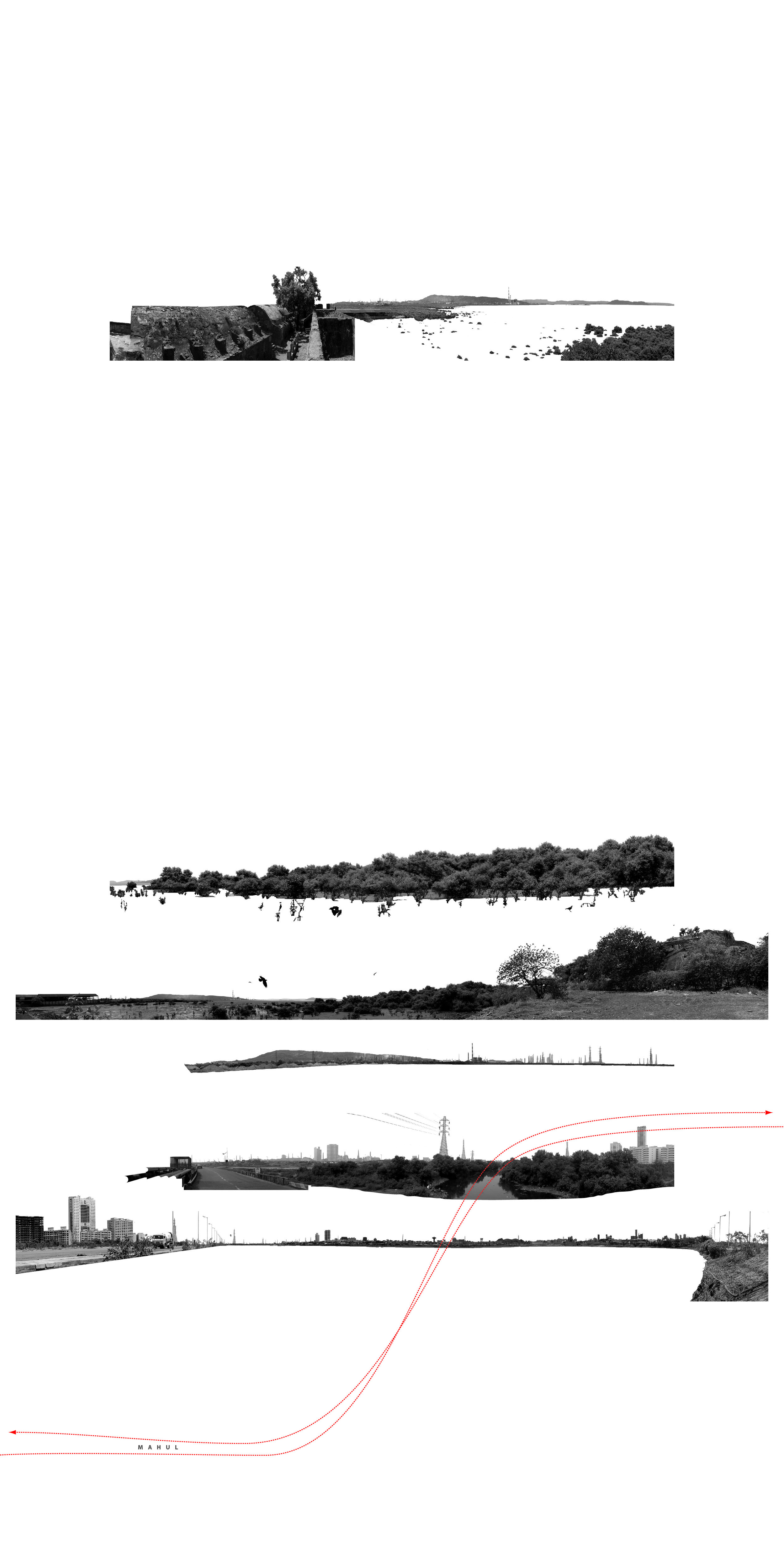

5. Sewri Fort

The Sewri Fort Project is anchored on a transect that begins from a rock considered one of the oldest in Mumbai and runs across one of the youngest and most fluid terrains of Mumbai – three miles of blue clay, mangroves, shells, salt marshes, salt pans and bird migratory routes, reaching to Neat’s Tongue, the English name for hill of Trombay ‘from the singular resemblance it bears to the tongue of an ox.’ The fort, located on the rock, kept vigilance on this line before both its ends were consumed by oil installations and its middle became increasingly firmed by land fill. The project returns the fort to being a point of vigilance across a dynamic terrain – a monitoring station for migratory birds and a starting point of walkways and boat routes into the mudflats and mangroves. It proposes making the Mahul Road the desired alignment of a route across the flats to Trombay and beyond; and it suggests that developments here work with alternating fingers of mangrove-cultivated gradients and biotic treatment fields as their necessary open space in an estuary rather than indulge in blanket reclamations of land.